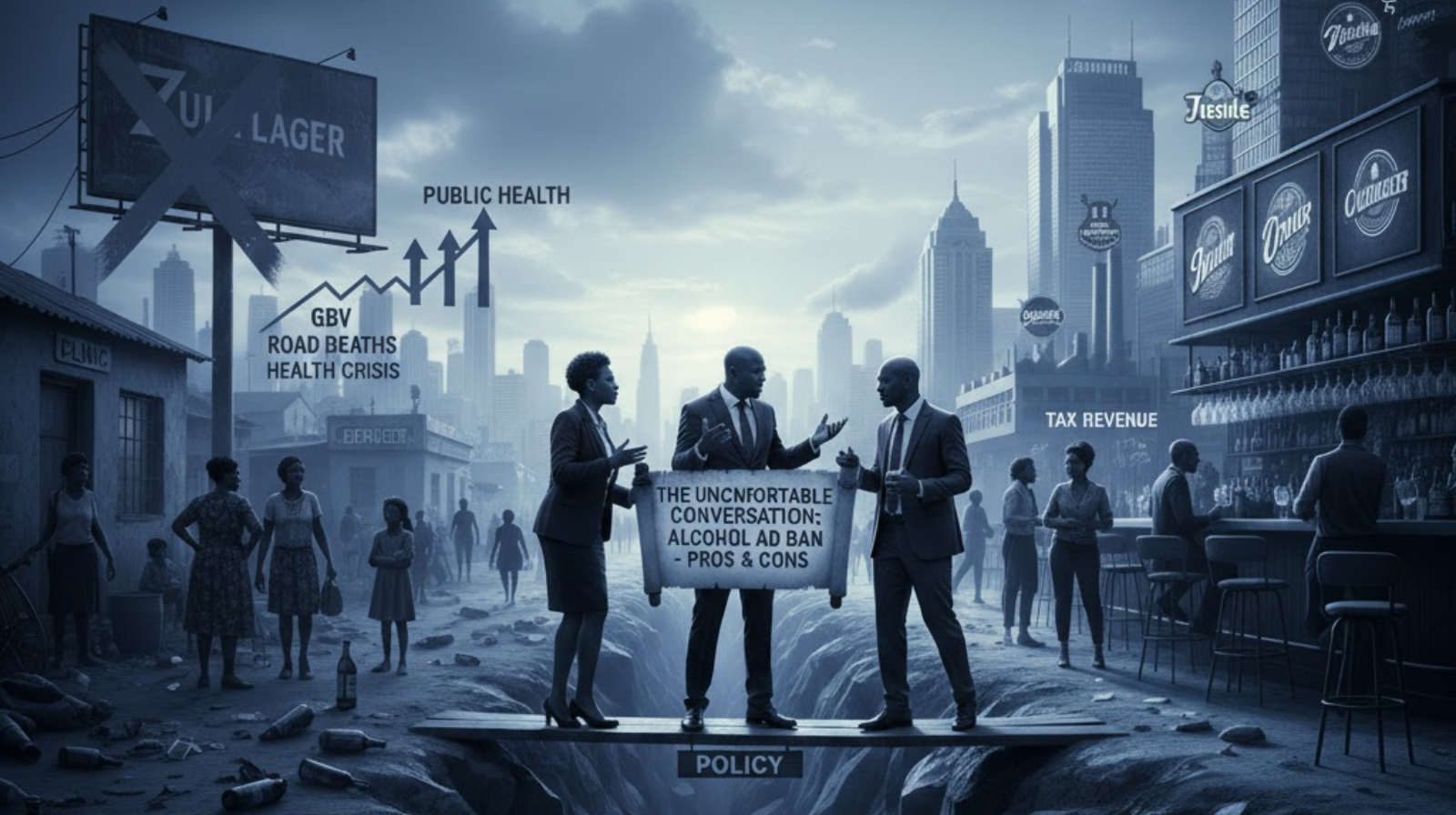

The proposal by the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) to impose a sweeping ban on alcohol advertising—covering television, radio, billboards, sports sponsorships, and digital media—has ignited a critical debate in South Africa. This controversy pits the urgent need to address the nation’s alarming rate of alcohol abuse and its attendant social harm against the economic and communicative freedoms essential to a robust market. While the move echoes the historical success of tobacco advertising bans, opponents, notably the Liquor Traders Council, raise valid concerns about economic damage and the effectiveness of advertising restrictions alone as a public health measure.

Working for an Alcohol-Safer South Africa (WASA), through the insights of its office bearer Maurice Smithers, offers a necessary middle ground, framing alcohol as an ancient, ubiquitous, and deeply ingrained drug—not merely a social beverage—that requires a holistic, multifaceted approach to management. The question is not if we should act, but whether a blanket advertising ban is the most effective and justifiable first step.

Alcohol: An Exceptional Drug with Exceptional Harm

WASA correctly positions alcohol as a unique drug. It is not an imported commodity like tobacco, opium, or dagga (cannabis), which originated in specific regions and later spread. Alcohol has been part of the human condition across virtually every culture globally, making its removal practically impossible, as evidenced by the failed Prohibition experiment in the US (1920–1933).

This historical context, however, does not negate its profound danger. Citing the seminal research by Dr. David Nutt, Smithers notes that alcohol consistently ranks tops in causing both individual and societal harm compared to two dozen other psychoactive substances. Crucially, it is one of the few drugs that causes more harm to society than to the user—a point highlighted by the link between intoxication and violent crime, road deaths, and domestic abuse.

The Illusion of “Responsible Drinking”

A core point of contention is the industry’s use of the term “drink responsibly.” WASA views this as a deliberate act of shifting corporate responsibility entirely onto the user. By focusing solely on individual behaviour, the industry mirrors the argument of the gun lobby (“guns don’t kill people, people kill people”), thereby dismissing the environmental and social pressures—including peer pressure, adult modelling, and advertising—that heavily influence how and why people drink.

The Case for Banning Alcohol Advertising

The EFF’s proposal, which is not unprecedented (it was tabled by then-Health Minister Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi in 2013), rests on the proven impact of marketing, particularly on young people.

Advertising does not just promote a brand; it glamorizes the behaviour. It creates aspirational scenarios of success, attractiveness, and belonging, showing the “first drink, not the last.” In a country where an estimated 60% of drinkers engage in harmful or binge drinking, this pervasive glorification contributes to a national culture that minimizes the risks of alcohol and normalizes its excessive use.

Countries like France, Norway, Russia, and Sweden have already implemented complete statutory bans, while others like Canada and Ireland have partial restrictions. The argument from public health advocates is that even in a well-regulated society, advertising is so effective that it inherently contributes to harm, necessitating its removal to protect public welfare.

The Enforcement vs. Legislation Dilemma

The most potent counter-argument, often voiced by those concerned with economic and communication freedoms (including media and advertising interests), is that the EFF’s bill is a classic example of “wallpapering a big crack.”

The Liquor Traders Council and critics argue:

- Enforcement Failure: South Africa already has laws governing drunk driving, liquor outlet licensing, and operating hours. The issue is not a lack of law, but a consistent, predictable failure of enforcement. Introducing a new, stricter law—like an ad ban—while ignoring the non-implementation of existing regulations is merely performative action. It restricts the freedom of those who comply without affecting the law-breakers who fuel the problem.

- Economic Rights: A blanket ban infringes on the right of a legal industry to promote its product. If a product is legal, the initial assumption must be that its responsible promotion should also be legal. Restrictions on who, where, and when the product is advertised are acceptable, but a total ban is seen as an overreaction that harms legitimate businesses.

The Holistic WHO Strategy

WASA agrees that an ad ban is not a “silver bullet.” The World Health Organisation’s Global Strategy to Reduce Alcohol Harm (2010) explicitly states that effective intervention requires a package of measures, not a single action.

The WHO’s “Best Buys” for reducing alcohol harm are:

- Restrict/Prohibit Advertising and Sponsorships.

- Reduce Availability (fewer outlets, restricted hours).

- Increase Cost (through taxation or minimum pricing).

Enforcement and awareness campaigns are also vital components. Therefore, the most pragmatic solution involves a whole-of-government approach where political will is mustered to implement all three levers simultaneously. The EFF’s bill addresses only one pillar, leaving critical issues like the current non-enforcement of drunk-driving laws and illegal liquor sales unresolved.

Conclusion: Balancing Rights and Responsibility

The debate ultimately hinges on a fundamental conflict of rights. Smithers suggests that a government’s responsibility to protect society must predominate, implying that the economic right of an industry to advertise an inherently harmful substance is secondary to the right of the majority (and society as a whole) to be protected from that harm.

However, critics caution against the dangerous precedent of always preferring the rights of the majority, arguing that constitutional rights—including the freedom of commercial speech—are specifically designed as protection for the minority against the will of the majority.

The practical reality in South Africa is that its pervasive alcohol abuse crisis demands immediate, hard-hitting action. While a complete advertising ban has been successful elsewhere and may be necessary as part of a final push, prioritizing the consistent, predictable enforcement of existing laws (drunk driving, illegal outlets, underage sales) would deliver immediate and verifiable public health benefits without the contentious legal and economic fallout of a total ban on legal commerce.

The EFF has succeeded in injecting urgency into this uncomfortable conversation. The challenge now lies with policymakers to implement a holistic strategy—as advocated by the WHO—that combines sensible restrictions on marketing with effective enforcement and pricing controls, ensuring the entire social infrastructure works to build an alcohol-safer South Africa 🇿🇦.